By John Groot

While there actually is no ancient Chinese curse that translates to “May you live in interesting times,” the idea that major historical events can mean chaos and grief to everyday folk is widely understood. One person who knows this well is Taiwanese-born doctor and amateur historian Hong-Ming (H.M.) Cheng. He and his family have had the rare position of not only being documenters and reporters of Taiwan’s history, but also participants in it, which gives the articles in H.M.’s (aka Eyedoc) Tamsui history blog “The Battle of Fisherman’s Wharf” a rare depth and insight. His ancestral lineage traces back to Koxinga’s half-brother, and members of his extended family have lived in or near Tamsui for hundreds of years. Some of them could have seen famous characters like Canadian missionary George Leslie Mackay or British tea merchant John Dodd on the street, or heard the cannon fire during the French barrage on Tamsui on October 2nd, 1884 with their own ears. Interesting times indeed! But this proximity to history also came at a great cost to the family, especially during World War II in the Pacific Theater – the Pacific War.

TAMSUI SHRINE

Many families experience tragedy during war, but a family of historians documents it. Shinsei Maru Story is a book by H.M. Cheng to honor his father Dr. Cheng Tze-Chang, who died when H.M. was still an infant, and his mother Mrs. Stella Yu-Yeh Wu Cheng, who bore a lifelong sorrow for the man she had loved and married in Japanese-occupied Taiwan. When she passed away in 2008, she left H.M. some hitherto unshared old photos and memoirs of their early marriage years in Tamsui amid the intensified Japanization of World War II.

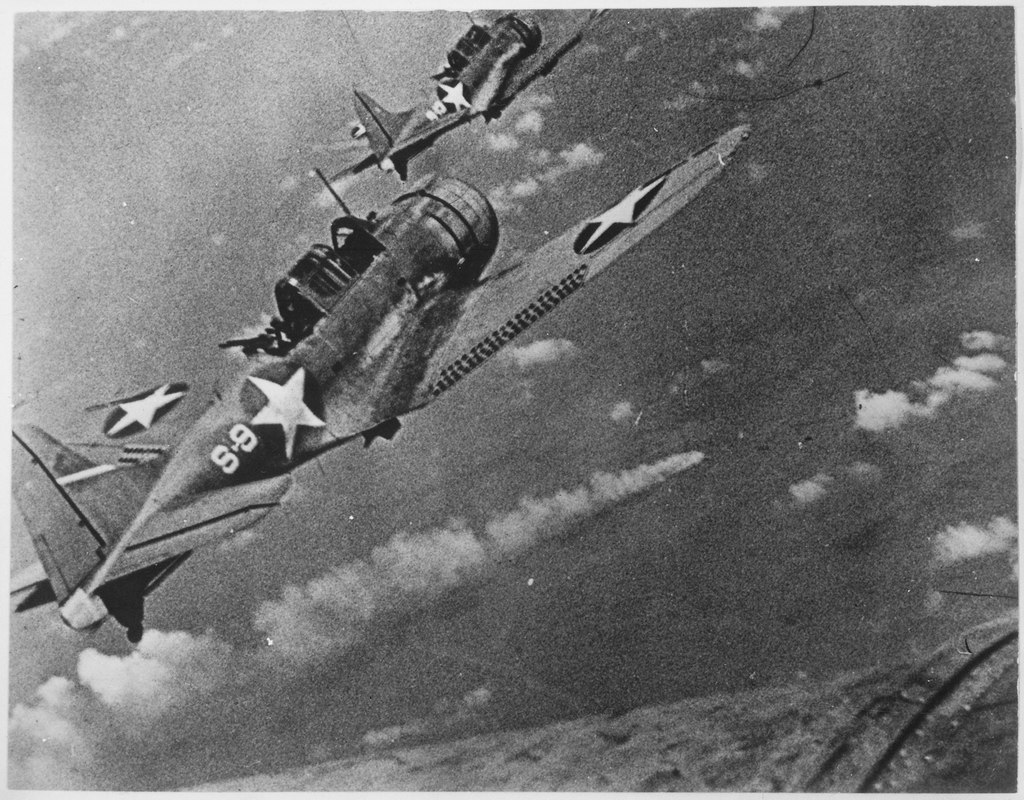

H.M. returned to Taiwan from the United States in 2008 to dig deeper into his family history, a process he had started in the United States the year before. What he uncovered was that, as a physician (like H.M. himself) Cheng Tze-Chang had been conscripted to serve the medical needs of staff at a far-way outpost of Imperial Japan, the oil-fields of Balikpapan in Borneo. But he never got there: On January 12, 1945, his ship—the eponymous Shinsei Maru, one of many with the same name—was sunk by an American aerial attack off the coast of Indochina (Vietnam.) Cheng Tze-Chang, along with hundreds of other medical and other personnel, was killed.

H.M. also discovered that his father’s name was listed at the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, along with millions of others who died in military service of the emperor. So, in 2008 and 2009, he visited the shrine to pay homage to his father, completing his journey of filial piety to both parents. Published in 2020, Shinsei Maru Story documents this entire journey in detail. It is based on primary historical sources and meticulous research. But there is also a deep line of sadness and loss that runs through it, very personal to the author and his family—one tiny particle of the great tragedy of the Pacific War.

It is also a fascinating window into the Japanese colonial era in Taiwan, seen through the eyes of H.M.’s mother and other family members who lived at that time. Thanks to H.M. Cheng for making the e-book freely shareable for the curious to enjoy learning from, in a spirit of respect for the serious family matters it discusses.

Two choices for free download:

1) A link: Free download of Shinsei Maru Story.

2) Direct download of the file. It appears blank because the

first page is blank, but the file is complete.

Additionally, as the whole context of the story is relevant to a larger discussion of Taiwan’s collective memory of being a colony of Imperial Japan, I have attempted a preliminary exploration of this topic, below.

Part 2

A Strange Affinity: Taiwanese Views about Colonial Japan

For most Westerners, the dominant narrative about Japan in World War II goes something like this:

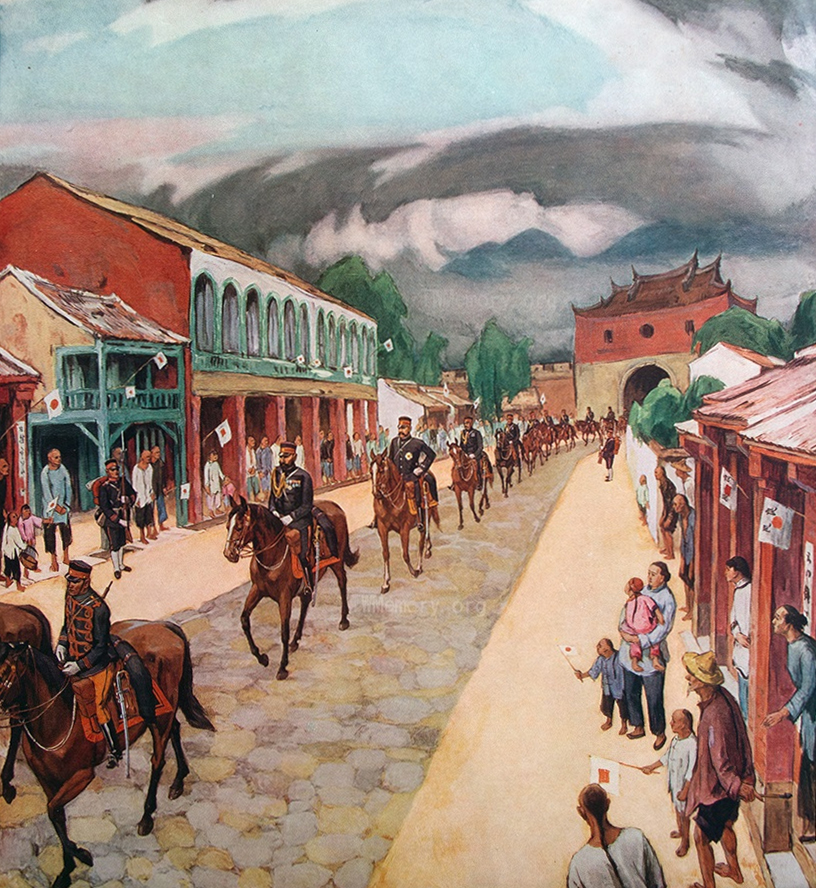

The Empire of Japan was a belligerent, militaristic state that expanded its territory through intimidation and conquest, taking over Taiwan in 1895, Korea in 1910, and Manchuria in 1931. It then committed the full-blown invasion of China in 1937—considered by many scholars as the beginning of World War II—grabbing considerable swathes of territory, including Beijing, Shanghai, and Nanjing. In 1940, the empire also took over French Indochina, with the approval of Vichy France.

Of course, the big power play was on December 7th, 1941, with the surprise aerial attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. In the following hours, Japan also launched attacks on the U.S.-held Philippines, Guam and Wake Island, the Dutch Empire in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia,) Thailand, and on the British colonies of Borneo, Malaya (Malaysia) and Hong Kong. Over the following weeks and months, they kept on the offensive. This was a war intended to build an empire spanning the entire east coast of Asia, and the waters and islands of the western Pacific, called “The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.”

PEARL HARBOR

By US Navy, Office of Public Relations

But they picked a fight with the wrong guy. Undaunted, and galvanized into furious unity, America mobilized its economy and military, and sailed across the wide Pacific to go toe-to-toe with the Japanese.

Easier said than done. The Japanese military was fanatical, following a twisted form of bushido, in which war was pure brutality. Like the samurai, fighters would almost never surrender in battle, even when facing their own destruction. In fact, they would often embrace their death in a last-ditch banzai charge or kamikaze attack.

Much darker was the atrocious treatment of enemy soldiers and civilians. Millions of Chinese died under Japanese occupation. Japanese forces killed perhaps 300,000 in the Nanjing Massacre of 1937–38 (aka Rape of Nanjing,) and 100,000 in the Manilla Massacre of 1945, to name but two examples. Many tens of thousands of women, from Korea, China, Australia, Taiwan, and other nations, were forced into sexual slavery in brothels as “comfort women” for Japanese troops. Many of them died or became sterile due to the abuse. Some of the worst evils of the so-called “Japanese Holocaust” were done by Unit 731, based in the puppet state of Manchukuo in north-eastern China, which performed sadistic biological, chemical, and conventional weapons experimentation on prisoners, as well as tortures such as vivisection. The Japanese also had “hell camps” and “hell ships” for enemy POWs, whom they treated worse than farm animals, working many to death in conditions of disease, malnutrition, and constant abuse.

This is the kind of enemy the Americans—and their allies, the British, Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, and others—were up against. But despite massive hardships, the Allies, especially the US Marines, were tough enough for the job. Starting with strategic victories in the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, they slowly but surely took down the Japanese war machine plane by plane, ship by ship, and island by island, each battle harder than the last—and none harder than Okinawa.

With US airbases now in range of the principal islands of Japan, the stage was set for the grand finale, the fire-bombing of 66 Japanese cities, culminating in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, respectively, 1945.

Japan, crushed, surrendered. The Americans occupied the country, which kept its beloved emperor but renounced war for all time. Over the decades, it developed into a peaceful, prosperous democracy and a loyal ally. It was a happy ending to the Pacific War, although we must never forget the evil that happened, nor the sacrifice of the brave service men and women that made victory possible.

This, then, is the familiar Western story, told in thousands of books, movies, and classrooms. Of course, like all narratives, it consists not only of facts, but also of which facts are focused on, and how they are framed or interpreted. This familiar Western narrative is not wrong, per se; but a world war is a huge and complex thing, and a variety of viewpoints is inevitable. As former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe said in April 26, 2015: “Things that happened between nations will look different depending on which side you view them from.”

Diversity of Viewpoints

In the Philippines, a former Japanese colony, most people agree that the Empire of Japan was evil. But just like most Americans, modern Filipinos are happy to let the past go and treat today’s Japan as the democratic and liberal country it has become.

On the other hand, China and Korea still have grudges with Japan, which erupt from time to time, usually about issues such as high-profile visits to Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine, or any nuances in the language of apologies by the Japanese government that seem to downplay the extent of wartime atrocities. China also actively indoctrinates its citizens to keep their hate for Imperial Japan alive in the present day, and weaponizes this sentiment against modern Japan’s strategic alignment with the United States.

But Taiwan, of all Japan’s former colonies, is an outlier. The “beautiful island” has maintained, over the years, and in the aggregate, a uniquely positive perspective on its colonial period, 1895–1945.

Many old-timers who had lived through that era looked back at those “good old days” with nostalgia. Although most them have now passed away, that was not before had shared their feelings of the Japanese as “tough but fair” and “better rulers than the mainlanders” with their families. Quite a few Taiwanese had even embraced full-on Japanization. Taiwan’s first locally-born president, Lee Tung-hui, went to university in Japan and became a second lieutenant in the Imperial Japanese Army in charge of an anti-aircraft gun in Taiwan in 1944. When he met former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, he told him: “Before 1945, I was Japanese.”

Meiji Magic

A lot of this pro-colonial sentiment can be put down to the indoctrination by the Imperial Japanese government of Taiwan, which pursued an ever-intensifying policy of cultural assimilation. But there is more to it than that.

It is well known that a profound modernization of Taiwan was begun under the leadership of Taiwan’s third Japanese governor-general, Kodama Gentarō, and his minister of civil affairs, Gotō Shinpei, both in office from 1898 to 1906. In particular, it was Gotō’s “Meiji spirit” that led to the transformation of Taiwan from a chaotic and unhealthy backwater to the model colony that Japan desired.

With Kodama’s full support, Gotō’s accomplishments were truly impressive. In addition to basic improvements in public health like creating hospitals, managing opium addiction, and developing modern infrastructure for sewage and drinking water, Gotō, per Wikipedia: “established the economic framework for the colony by government monopolization of sugar, salt, tobacco and camphor and also for the development of ports and railways. … By the time Gotō left office, he had tripled the road system, established a post office network, telephone and telegraph services, a hydroelectric power plant, newspapers, and the Bank of Taiwan. The colony was economically self-supporting and by 1905 no longer required the support of the home government despite the numerous large-scale infrastructure projects being undertaken.”

Later administrations continued modernization with similarly ambitious projects, including the completion of the Western Trunk Line railroad from Keelung to Kaohsiung in 1908, the development of high-yield Japonica rice in the 1920s, the establishment of Imperial Taihoku University (the forerunner of National Taiwan University) in 1928, and the completion of the Chia-nan Canal irrigation system in western Taiwan in 1930. Taiwanese alive during this time could not have failed to be impressed by these changes, which brought tangible improvements to their quality of life.

Rosy Retrospection

Of course, these advances were not done out of altruism, but to make Taiwan into a strategic asset for imperial expansion. Taiwan was an important source of rice for Japanese troops, and the island’s airfields, ports, and coastal waters played a critical role in the invasion of the Philippines in 1942. The Meiji slogan was, after all, “Enrich the country, strengthen the military” (fukoku kyōhei). Gotō himself was a staunch defender of Japanese colonial policy in China, despite its many excesses.

Also, it should not be forgotten that, before the modernization of Taiwan truly began, there had been a forceful military occupation. Although Qing China had ceded Taiwan to Imperial Japan in the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, many on the island fiercely resisted their new rulers. Tens (some say hundreds) of thousands of ethnic Chinese militia members and indigenous fighters were slaughtered in the pacification campaigns from 1895–1915, although most of these were over by 1902. (Some indigenous resistance lasted until the early 1930s.) Mass murder and rape by Imperial Japanese troops were committed against villages who supported the rebels, or were simply in the area where they operated.

It is hard to know how widespread the knowledge of the slaughters and atrocities would have been within Taiwanese society. Much of the bloodshed occurred in the countryside or mountain areas, removed from coastal urban centers. In Taipei, business leaders like Koo Hsien-jung (founder of today’s multi-billion-dollar business empire the Koos Group) had actually invited the Japanese to take over to relieve the city from rampaging Qing soldiers from mainland China. It is unlikely that Japanese officials would have openly advertised their own side’s war crimes, or permitted pubic discussion of them. Hence, Taiwanese living during the colonial period could perhaps be forgiven for living in a rose-colored bubble.

Nor would there have been widespread knowledge of the treatment of POWs in Taiwan during World War II. According to researcher and Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society director Michael Hurst, Japan operated 16 prisoner of war camps (including two temporary camps) between August 1942 and September 1945. Hurst says that Japanese records show that 4,344 allied servicemen were held as POW’s in camps in Taiwan during this period, 430 of whom died in the camps and more afterward as a result of their treatment by their captors. The worst was at Kinkaseki (now called Jinguashih, a village on a mountain that rises above the coast in Ruifang District of New Taipei City, not far south of Keelung) where starved and beaten prisoners were forced to work in inhuman conditions in the copper mines.

However, after the end of the war, the truth was revealed, not only of evil deeds in Taiwan, but much fouler ones done in China and elsewhere. Many from the “mainlander” exodus to Taiwan 1949–1950 would have brought their own reports of brutality. The Chiang Kai-shek regime in Taiwan was initially very anti-Japanese, destroying many Shinto shrines, jailing wealthy “collaborator” businessmen like Koo Chen-fu, the son of Koo Hsien-jung, and even forbidding the screening of Japanese films for years. But this animosity didn’t last long, at least not publicly. It was China that the KMT were obsessed with, not Japan.

Taiwan President Ma Ying-jeou did briefly seem to try and resurrect anti-empire sentiment with memorial events and statements to the press in 2015—the 70th anniversary of the end of the war. This may have been an attempt to get Taiwan to shake off its “Japan-mania” and harmonize with China’s position. But it soon fizzled out, and under successive DPP-led governments, August 15 and September 2—the dates in 1945 when the Japanese surrender was first announced on a recorded radio broadcast by Emperor Hirohito, and when the Japanese Instrument of Surrender was signed on the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo harbor—pass in Taiwan each year with only a few small media events about Taiwan’s “comfort women” and a couple of routine press releases from the government.

There is close to zero general public interest in POW memorial events. Taiwanese have let the war go. Yet local tourists continue to flock annually in the millions to colonial-era-themed attractions like Hinoki Village in Chiayi, Hayashi Department Store in Tainan, and old streets with Japanese baroque architecture such as Dihua Street in Taipei and elsewhere. Why this persistent affection for the colonial period, and apathy about Japanese war crimes?

No one can definitively answer this question. But it is likely that a combination of factors prevented a strongly anti-imperial cultural movement from becoming entrenched in Taiwan.

One factor is that the KMT leadership of Taiwan was considered inept and kleptocratic in the initial years of rule. They displaced the Taiwanese elite, whom they distrusted, and then flooded the country with over a million refugees from the Chinese Civil War, which was hugely unpopular. To most Taiwanese living through the first decade of Republic of China rule, life in Japanese times might have seemed good in comparison, especially considering the social tensions after the 2 28 Incident and the subsequent White Terror. Furthermore, many among the Taiwanese elite had had friends and business partners among the Japanese community, another reason to be tactful in later years: people shouldn’t publicly criticize their friends, especially if acknowledging their misdeeds would also implicate themselves by association. Hence, better for the old-timers to just stick with the “good old days” trope and leave the rest alone.

A few decades on, Japanese purchases of Taiwan-made products, and the transfer of technology to Taiwanese vendors and subsidiaries, made a significant contribution to Taiwan’s economic miracle of the 1970s. So, even those with a “mainlander” background might have avoided speaking out about the war to avoid friction with their new business friends. Japan remains a very important business partner to this day.

There is also the fact that—unlike Korea and China—Taiwan before Japanese occupation lacked a clear and distinct sense of identity. Replacing the Qing’s inconsistent and corrupt rule with a “Meiji Taiwan” was arguably an improvement, in contrast to the humiliation felt by the Chinese and Koreans, whose own proud traditions were subjugated. Hence, Taiwanese were free to become avid consumers of modern Japanese culture—including anime and J-pop—during its renaissance in the 1980s and 1990s, without any bitter aftertaste of an historical grievance. This only added to the significant influence of Japan on Taiwanese music, a hold-over from the colonial era.

This 80s and 90s also coincided with the rise of Taiwan’s human rights and self-determination movement, which culminated in Taiwan’s first democratic presidential elections in 1996. The intellectual roots of this movement trace back to the “Taishō Democracy,” a period of liberalization in Japan—where many Taiwanese intellectuals attended university—and in Taiwan itself, which grew strongly from 1912–1926, under the short reign of the Taishō Emperor. Hence, leaders of the pro-Taiwanese-autonomy side of the political spectrum also tended to look back appreciatively at these times, in contrast to the Sinocentric narrative of the KMT.

Now, in 2024, with the threat of annexation by the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, sitting anxiously outside the US nuclear umbrella, attaches great value to Japan’s political and military support, such as it is. This is another reason to keep the tone of discourse positive.

Taken all together, this might be considered a list of compelling motivations for Taiwan to have looked away from the dark history of Imperial Japan. Focusing on the positive aspects of the empire might simply be described by Taiwan’s favorite adjective—convenient.

Visits to Yasukuni

Is it possible that Taiwan has also borrowed Japan’s own aversion to doing a deep dive into wartime guilt? Approximately 200,000 Taiwanese served the Japanese military in the war: some were conscripted, but many fought proudly for the emperor. A few were even guilty of war crimes themselves. At the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, 27,863 Taiwanese (many from indigenous communities) have their names listed, among a total of 2,466,532 people who died in the service of Japan in wars under the Meiji, Taishō, and Shōwa (Hirohito) emperors.

An interesting YouTube video by Hikelopedia about Taiwanese at Yasukuni.

The shrine is source of controversy due to the fact that among the names honored there are those of 1,066 war criminals, 11 of whom were convicted of class A war crimes by the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal. These include Japan’s ultranationalist war-time prime minister Hideki Tojo, and also Akira Mutō, implicated in both the Nanjing and the Manila massacres.

Hirohito (the Shōwa Emperor) eschewed any visits to the shrine due to that fact. But, per Wikipedia: “Former prime minister Junichiro Koizumi made annual personal non-governmental visits from 2001 to 2006. Koizumi’s expected successor, Shinzo Abe, visited the shrine in April 2006 before he took office. … Abe publicly supported his predecessor’s visits to the shrine, and he made at least one visit to the shrine during his term as prime minister.”

These high-profile shrine visits were criticized by China, Korea, and Russia as glorifying the nationalistic militarism that led to horrific abuses in World War II, atrocities that have often been downplayed by revisionist historians in Japan.

However, the Yasukuni Shrine was not intended to be a symbol of militarism, but rather as a way to honor the dead. Virtually every family in Japan has the name of a relative inscribed there, a sad reminder of the huge human cost that Japan paid for losing the war. Lee Teng-hui himself visited the shrine in 2007, to honor his brother Lee Teng-chin, who died as a member of the Imperial Japanese Navy in Manila in 1945. His name is there along with that of Cheng Tze-Chang, the father of Hong-Ming Cheng.

Coming Full Circle

As mentioned before, H.M. returned to Taiwan in 2008 to do family research and make his Yasukuni visits. During this time, he looked into the history and culture of Tamsui, where his parents got married and lived as a young couple. This knowledge is what led first to the creation of a blog in Mandarin about the Shinsei Maru in 2007, and then shortly afterward his famous English-language history blog, “The Battle of Fisherman’s Wharf” in 2009. It should come as no surprise then that there are quite a few posts in both blogs about civilian casualties from American aerial bombings of Taiwan in World War II. These air raids started in 1943, and intensified in 1944 and 1945, killing approximately 5,500 Taiwanese, according to Japanese records from that time. The attacks were part of a wider strategic aerial campaign in the Western Pacific, one which also sank the Shinsei Maru.

Other posts by H.M. (signed by his blogger alias, “EyeDoc”) talk about the sadness of the hundreds of thousands of Japanese residents of Taiwan—not just soldiers or bureaucrats, but people from many walks of life—who were deported back to Japan in 1946. Some of them kept in touch over the years, made nostalgic return visits to Taiwan, or had reunions in Japan decades later. While interesting as tidbits of history, the way these stories are told, their seemingly pro-Japanese tone, might rub some people the wrong way. After all, the Americans were the good guys, right?

Well, not during the war they weren’t, not to most Taiwanese. Afterward, when the bombs stopped, and friendly Americans offering aid money started coming in, that was another story. But all of that was so long ago. Taiwan is a different place now, and the Taiwanese have moved on—almost all of them. H.M.’s lingering resentment against American aerial attacks is understandable, considering that they cost him a father and his mother a husband. As he says in Shinsei Maru Story, “… for families of the war-dead, mourning is forever, for there is really no such thing as closure.”

In any case, whatever your personal perspective, Shinsei Maru Story is an authentic glimpse into that fascinating and tragic time in history.

—————————————————————————————————-